Political economy of debts and deficits (1): Introduction

In a series of texts I will touch upon some of the theoretical and empirical factors explaining the expansion of debts and deficits in many of the World's economies in the past 40 years. This has been adapted from my 2014 Public Finance lectures, and can serve as a reminder to my students. Today's post will provide and introductory overview of the argument, the next one will be focused on the common-pool problem and political instability, while the third one will present some of the main hypotheses explaining the rise of debts and deficits in the past 40 years.

The rise of debt

Government debt, much like government size, has increased in the past 40 years in many industrial economies. The rise of public debt has mostly been attributed to the rise in government size, and in particular running persistent budget deficits. The real question, for which we need to apply a political economy analysis, is why this was so?

The traditional theory of public debt was based on the argument of tax smoothing. Assuming that a country faces a transitory sharp increase in spending, the question arises whether it should be financed by increasing taxes so as to keep the budget balance unchanged, or should it be financed by borrowing, which would spread the increased tax burden over a longer period, assuming that the population does not want to leave all of the debt to its children. A trade off arises between a burden imposed on current voters or future generations. Given that taxes cause distortions which in most models are proportional to the square of the tax rate, it is better to finance the transitory spending by borrowing, and only modestly increasing taxes so as to cover interest costs and ensure repayment over a long period.

Essentially politicians can keep their promises of higher concessions to certain groups in three ways: higher taxation of current voters (unpopular), shifting spending from one group to the other (unpopular for the losers), or increase debt – which is essentially taxing the future generations. Increasing debt (borrowing) is the easiest outcome available since voters suffer from a fiscal illusion and tend to act rather myopically (shortsightedly), and will be less inclined to punish politicians immediately for accumulating debt (they are unaware and not well informed to punish such policies).

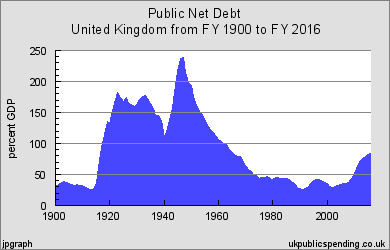

Wars are perfect examples of temporary spending pressures for which the tax smoothing argument makes sense (see Figures 1 and 2 below). As a result, the historical pattern of public debt dynamics in the past was a surge during a war, and then a gradual decline after the end of the war. Notice the effect of WWI and WWII in the UK on its debt-to-GDP levels, as well as the WWII effect in the US. Also notice how the current debt-to-GDP levels for the US are almost as much as they were during the war. That is indeed a reason for concern.

|

| Figure 1: UK Debt-to-GDP ratio, 1900-2016 |

|

| Figure 2: US Debt-to-GDP ratio, 1900-2016. The blue line represents state-level debt, red line local, while green is federal (national) debt. |

Since the 1970s, contrary to previous trends, public debt ratios in most advanced economies started to rise, despite the fact that there were no major wars in that period, and that GDP growth performance was quite strong (a high denominator should have lowered the total ratio, not increase it). Debt dynamics for selected countries can be seen in Figure 3.

The period from the 1980s onwards was called the Great Moderation for its low inflation rates and relatively high growth rates. It was a welcomed change from stagflation of the 1970s, however stronger economic performance still went hand in hand with debt accumulation.

In the current crisis higher debt levels are primarily the result of massive government fiscal stimuli done in 2008/2009 to combat the initial effects of the crisis (bank bailouts in the US, UK, Spain or Ireland are a good example – not shown in the graph). It is primarily because of bank bailouts and other adverse effects of the crisis that most European as well as the US government are facing unsustainable debt burdens in current times (and why their governments are obsessed with austerity, even though it’s being done the wrong way).

Japan is a case in point and a good indicator of what might be awaiting some European countries for the next few decades (it's debt to GDP is currently over 230%). The bubble burst in Japan in the 1990s triggered massive monetary and fiscal stimuli for the past 20 years which haven’t affected real economic growth at all, while Japan was stuck with a few deflationary episodes in addition to massive increases of government debt.

More recent trends for Eurozone countries appear below. One can see that the average debt ratio was above the Maastricht 60% limit (by about 10 p.p.) even before the very foundation of the Eurozone, which is interesting since the 60% debt-to-GDP limit was a primary condition of membership (in addition to a < 3% deficit to GDP). However countries were allowed to introduce the euro if they have exhibited declining trends of the debt and deficit levels at the time - otherwise Italy and Greece would have never been members in the first place (which in hindsight wouldn't have been that bad).

Thank you for your great job. This is the info I have been looking for.

ReplyDelete